Bonhoeffer and the Martyr's Method

On faith and fearless obedience

I originally published a version of this post in November 2024.

Also. . .if you’re one of the brave souls who’s been memorizing the opening verses of John’s gospel along with me, give verse 4 a go this week. I’ll offer some tips on this lost art next week.

A couple of years back, the internet was abuzz with the rumor that men typically think about the Roman Empire several times per week. I suspect there’s a type of Christian who thinks about Dietrich Bonhoeffer just as frequently.

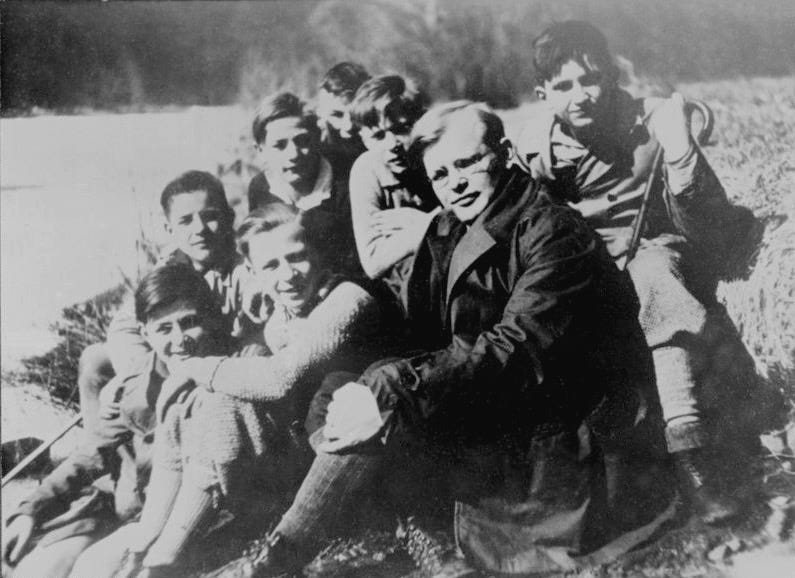

He’s given us plenty to think about. Immediately after Hitler became Germany’s Chancellor in 1933, Bonhoeffer warned in a radio address against the dangers of elevating a leader to messianic status. That message was cut short—likely by government censors. Just four years later, he published The Cost of Discipleship. The book reminded believers that following Jesus necessarily involves repentance and suffering. Bonhoeffer, of course, would go on to pay the ultimate price for his commitment to Christ. Unwilling to bow to the regime, the Nazis executed him in 1945.

Eighty years later, he remains a towering, if confounding, figure. His reading of Scripture is too straightforward for theological liberals, his theology too eclectic for fundamentalists. While he lived with unwavering faith, his journals occasionally reveal searing doubts. He wrote movingly about marriage, though he, himself, died while engaged, still waiting to wed.

Bonhoeffer’s courage, however, was uncomplicated. He refused to be complicit with a government that sought to manipulate Christians and twist the faith.

“Do not be afraid,” along with its variations, stands among the Bible’s most frequent commands. In Matthew 14, when Peter tries to walk on water, it’s his fear that sinks him.

[Jesus] said, “Come.” So Peter got out of the boat and walked on the water and came to Jesus. But when he saw the wind, he was afraid, and beginning to sink he cried out, “Lord, save me.” [emphasis mine]

Matthew 14:29–30

Jesus then rescues Peter, famously responding, “O you of little faith, why did you doubt?” In other words, there is a close connection between fear and doubt. In the following post on Bonhoeffer, I wrestle with how Scripture connects saving faith to our faithful works. In sharing it again, I hope that, by God’s grace, it will help you to live—and act—with renewed faith and courage.

If you don’t read the Bible every day, try this reading plan. Just one chapter each day will take you through Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John by Christmas.

Subscribe to The Long Renewal and you’ll get insights each week that align with what you’re reading.

Is It True That All You Need Is Jesus?

I’ve shared that the phrase all you need is Jesus was nearly ringing in my head the night I got saved.

It was part of what a street evangelist had told me years before:

You don’t have to do anything. You don’t have to prove anything. All you need is Jesus.

My salvation experience was overwhelming and convincing. Over the years, especially during difficult stretches, my memories of that night have helped anchor me. They’ve assured me that, yes, God is not only real, but he’s also active in our day. He truly does give grace to those who don’t deserve it.

Yet today, around fifteen years later, when I think of that phrase all you need is Jesus, I can’t help but ask:

Is it really that simple?

Are those words a helpful reminder that the Bible is, first and foremost, a story about God and not us? Could the saying help us to remember that we can never outgrow God’s grace?

Or is it a bit misleading? Could it be too tidy? Might it be used to justify half-hearted Christian living? After all, it takes a lot of effort to fight against sin every day. Conversely, it’s easy to rattle off a phrase like all you need is Jesus, and just like that, you can whitewash your laziness.

That phrase meant everything to me the night I got saved. It continued to anchor me in the years that followed. But, again, is it really that simple?

To think through these questions, I’ll use a contrast. First, I’ll touch on my experience as a new Christian in the early 2010s. All you need is Jesus fit pretty well alongside the preaching I received at that time.

Next, I’ll draw from a sermon that I heard more recently. It was about Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the German pastor who was martyred by the Nazis. To strengthen Christian ministers so they wouldn’t capitulate to Hitler, Bonhoeffer organized underground seminaries. He hoped that through rigorous training, prayer, fasting, and psalm singing, believers would remain steadfast—even in the face of extraordinary government pressure to cave.

Although the backdrop of World War II Germany makes Bonhoeffer’s story unique, it raises a question that applies in every era:

If all you need is Jesus, then what’s the purpose of the kind of heavy spiritual lifting that Bonhoeffer urged?

Old Memories of New Calvinism

Although I was Catholic when I got saved, within a couple of years I found my way to a church heavily influenced by New Calvinism. How I got from one to the other might be worth recounting at some point, but that won’t be the focus here.

It was 2010 when I showed up at my new church. Although I hadn’t heard of New Calvinism or “Young, Restless, and Reformed,” I happened to arrive right around the peak of that movement’s energy and influence. Names like John Piper, Timothy Keller, and, yes, Mark Driscoll, came up all the time.

My church emphasized the futility of trying to earn God’s favor through your own efforts. We were reminded—correctly—that the forgiveness of our sins was only possible because of Jesus’ death on the cross. We were taught that we couldn’t outgrow the good news of the salvation by grace. In other words, it was a mistake to think that after trusting in Jesus and receiving his forgiveness, you could simply move on to doing good Christian deeds. No matter how many faithful works we might pile up, we still needed to rely on God’s grace. As one common saying put it, we’d always be at the foot of the cross.

That much, I think, few Christians would take issue with.

So all you need is Jesus, after all, right?

The problem is that even essential truth can be distorted. It’s necessary to understand that human efforts can’t earn God’s forgiveness. But when you camp on that particular point, it’s possible to accidentally cast suspicion on good, faithful works.

I saw this mistaken tendency show up at times. I find the 2013 observation by Paul Washer, a pastor sympathetic to New Calvinism, helpful:

The lifestyle of at least some young reformers borderlines on an antinomianism that flaunts its supposed freedoms and shuns rigorous piety as little more than bondage to the Law.

By antinomianism, he means a distorted form of the faith that asserts Christians don’t need to obey any moral laws. According to this misunderstanding, if you trust in Jesus for your salvation, it won’t make any difference whether you manage to break free of sinful patterns in your life. All your sins are forgiven regardless, after all.

Many churches have been influenced by New Calvinism in different ways and to various degrees. I’m not suggesting that all churches touched by the movement threw the importance of moral obedience out the window. Overall, I don’t think that mine did. But at times I saw glimpses of what Washer describes.

And my broader point is that a person could slip into a dismissive attitude toward moral obedience and keep right on claiming what I heard years before from that street preacher:

You don’t have to do anything. You don’t have to prove anything. All you need is Jesus.

All You Need Is All of Jesus

Of course, if you read the Gospel accounts, you quickly discover that Jesus was instructing his followers to do lots of things. To take just a few examples from Matthew, believers are to pray,1 to forgive those who wrong them,2 to love their enemies,3 and to make more disciples.4

If all you need is Jesus, maybe we should strive to obey all of Jesus, meaning all that he said.

And while we may intend to pray, how vibrant are our prayer lives, really? We know we’re supposed to forgive, but it’s so much easier to hold a grudge. And what would it even be like to love our enemies? Does anyone really live like that?

When we realize how difficult it is to obey Jesus, the temptation to settle for a flat understanding of the faith can emerge. An over-simplified understanding of all you need is Jesus has a certain appeal. That’s because living as Jesus instructs us to and making even more disciples who live like that is very, very hard.

Bonhoeffer’s Rigorous Path

If anyone understood the difficulty of making faithful disciples, it was Dietrich Bonhoeffer. Two years ago, I was reminded of this in a sermon that centered on the German’s life and practices. Early on, the pastor brought up 1 Timothy 4:7–8:

Train yourself for godliness. For while bodily training is of some value, godliness is of value in every way, as it holds promise for the present life and also for the life to come.

You might expect this verse to be used along with a modest encouragement like, “Now please go home and read your Bibles a little more.” But in this particular message, the pastor connected the idea to Bonhoeffer’s courageous life and his rigorous style of ministry.

The sermon drew from a story in Jon Tyson’s book Beautiful Resistance. It recalls a historian named Wilhelm Niesel, who traveled to the seminary near Finkenwalde, Germany for a firsthand look at Bonhoeffer’s ministry.

In 1935, Bonhoeffer had founded a Christian community designed to reflect the ethic of Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. Participants also had to develop the spiritual tenacity to resist capitulation to the Nazis. As one writer puts it, “Hitler did not merely want to rule Germany politically; rather he wanted to control the hearts and souls of its citizens.”5 In response, seminary life was strenuous. It required prayer, Bible study, and communal worship at set times. Some, like Niesel, wondered whether so much rigor was really necessary.

To make a vivid case for his approach, Bonhoeffer took Niesel to a hill where they could see German soldiers training for battle. Fighter planes were taking off and landing. Soldiers were marching in formation. Bonhoeffer explained to Niesel that the Nazi soldiers were practicing disciplines that trained them “for a kingdom . . . of hardness and cruelty.”6 His view was that Christians needed to respond with a life of biblical discipline. Bonhoeffer summed it up bluntly:

What we're doing at the seminary has to be stronger than what Hitler's doing in forming his army.7

Grace and Grit

If you’re hoping I’ll tie all of this together with a bite-sized takeaway, you’re going to be disappointed. A deep dive into the topics here (grace, Christian obedience, Bonhoeffer’s story, Christians caving to ungodly government, etc.) could fill many books. I’ll offer a few thoughts meant to provoke deeper questions about both grace and obedience.

First, we can’t overstate the importance of God’s grace. Whatever efforts we make to obey God, these are only possibly because of the gift of grace that God gave us first. There’s good reason why many Christians regularly bring up Ephesians 2:8-9:

For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God.

In well-meaning response, some Christians become concerned that vigorous efforts at obedience will undermine our appreciation of God’s grace. I’ve heard it said that believers generally lean toward legalism (over-emphasis on godly obedience) or license (laxness with regard to Jesus’ commands).

I’ve written about why I think that formulation is overly simplistic. But even if it’s a fair generalization, the idea can still nudge us in the direction of a serious mistake. It can lead to the assumption that if a believer makes a lot of effort to obey God’s word, that person probably has a legalistic streak. This, in turn, sets up mediocre, half-hearted Christian living to appear as the ideal.

After all, as the logic goes, too little obedience might be a sign of spiritual carelessness or license. But on the other hand, too much obedience might be a sign of equally dangerous legalism. Splitting the difference, then, appears to be the sweet spot. The wisest option, according to this logic, is to make some effort to grow in Jesus but not too much. After all, why work hard and risk getting labeled a legalist? Especially when you could ease up a bit and enjoy the acceptance of more Christians.

But Scripture confronts the notion that zeal for good works is a warning sign of legalism. In fact, it connects salvation by grace directly to our active, faithful response.

I brought up Ephesians 2:8–9 earlier. This time I’ll include verse 10 [emphasis mine]:

For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them.

A similar bridge appears in Colossians 1:29:

For this I toil, struggling with all His energy that He powerfully works within me.

The author of Colossians, the apostle Paul, pours extraordinary effort into his ministry. Nonetheless, he knows that his toil ultimately reflects God’s power working through him.

Recall Bonhoeffer’s quote about how the disciples’ efforts at the seminary needed to be stronger than the Third Reich army. Without the power of God, his notion is ludicrous. But with the Holy Spirit’s involvement, who’s to limit what the Lord might do through our efforts?

Finally, Bonhoeffer’s era is not as unusual as it seems. Those of us who’ve known relative peace in our lives might view the rise of Nazi Germany as a terrible exception. And thankfully, in many ways, it was.

But the Bible makes clear that an unseen battle between good and evil continues to unfold throughout all of history. The demonic powers that made Hitler possible might be restrained or more subtle in our time and place, but they’re still around.

Christians rely on God’s grace in all things. Yet, we should also approach life with the discipline of an athlete, as the apostle Paul describes in 1 Corinthians 9:

Do you not know that in a race all the runners run, but only one receives the prize? So run that you may obtain it. Every athlete exercises self-control in all things. They do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable. So I do not run aimlessly; I do not box as one beating the air. But I discipline my body and keep it under control, lest after preaching to others I myself should be disqualified.

1 Corinthians 9:24-27

Run the race, brothers and sisters. Train like the heroes of the faith. Let your hearts be free of fear. And by the grace of God, receive the everlasting prize.

Matthew 6:9-13

Matthew 6:14

Matthew 5:44

Matthew 28:19-20

Gaylon Barker, Dietrich Bonhoeffer: Theological Education at Finkenwalde 1935-1937 (quoted in Jon Tyson’s Beautiful Resistance)

Charles Marsh, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (quoted in Jon Tyson’s Beautiful Resistance)

Charles Marsh, Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer (quoted in Jon Tyson’s Beautiful Resistance)

Thank you David, I think this list is just what I was looking for to start my day x