Is a Republic for the Virtuous?

Or the virtue-less?

Two weeks ago, I pointed out that the words we translate church and gospel had political meanings in the first century. This, I think, makes it hard to claim that politics can or should be walled off from Christianity.

Last week, I shared examples of how even non-believers are realizing that the decline of Christian morality has harmed our country and our culture. I made the case that the virtues the Bible requires for leaders in the church are essentially the same as those it puts forward for political leaders.

But where, exactly, does all of that land us?

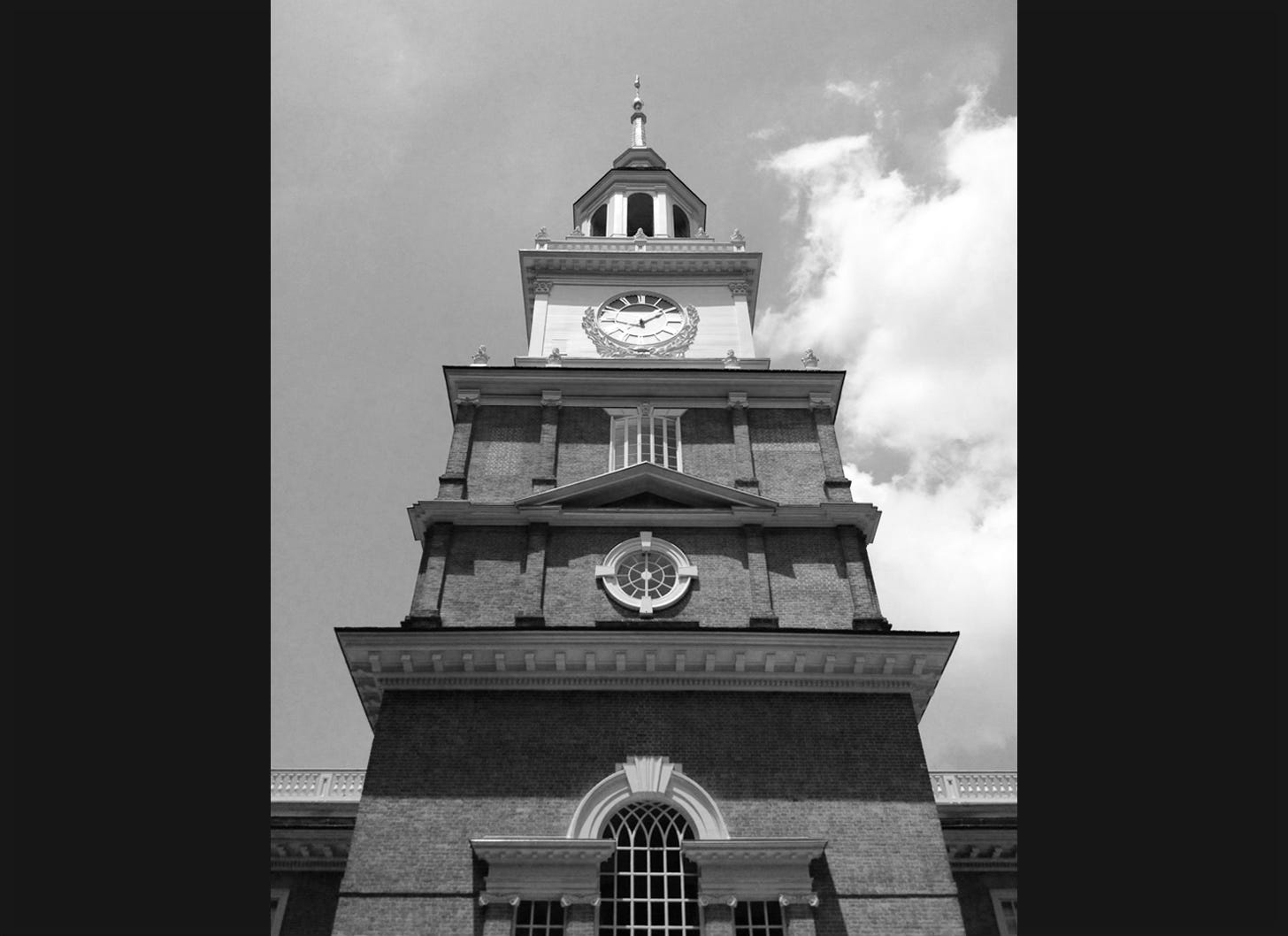

In Philadelphia during the sweltering summer of 1787, of course.

Yes, I’m taking a flying leap from broad strokes biblical ideas to America’s Constitutional Convention. But it’s a jump that makes sense, I think, given where we left off last week.

That’s because the Bible’s insistence that political leaders should be virtuous (Deuteronomy 17:14–20) raises an obvious question: Where are you going to find any like that?

Some today imagine that the era of the American Founders was overflowing with Christian morality. There’s a half-truth here. Since many of the universities of the day were also seminaries, biblical truth was, at that time, much more interwoven with intellectual life than it is today. But there’s also more to the picture. Church membership was considerably lower then than it is today. Yes, you read that correctly. Fewer than 1-in-5 Americans were actively involved in a church in the late 1700s.

And the Founding Fathers didn’t have any illusions about human nature. As James Madison wrote in Federalist No. 51:

What is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary.

Other Founders agreed. What follows are a sampling of quotes drawn from Robert Tracy McKenzie’s book We the Fallen People: The Founders and the Future of American Democracy:

Ambitions and lust for power. . .are predominant passions in the breasts of most men.

– Samuel Adams

Ambition, in that day, was viewed very negatively. It was regarded as the force that was unleashed when virtue retreated. Patrick Henry concurred with Adams, writing that he dreaded “the depravity of human nature.” Alexander Hamilton saw “the folly and wickedness of mankind.” Meanwhile, George Washington was convinced that “the motives which predominate most in human affairs are self-love and self-interest.”

McKenzie goes on to quote similar sentiments from Roger Sherman, George Mason, John Jay, and Benjamin Franklin. Naive, these men were not. Nor were they all deeply religious men. But each was a clear-eyed observer of human nature.

Thus, the Constitution established three separate branches for the federal government of the United States. The legislative branch, or Congress, would make laws. The executive branch, very visible today because the president leads it, was to make sure those laws were carried out. And finally, the judicial branch, or the courts, would interpret the law.

A system of checks and balances was created to prevent any one branch from overpowering the others. For example, a bill passed by Congress had to be signed by the president to become law. Yet, even if the president rejected a bill approved by lawmakers, Congress, with a large enough majority, could override the president’s veto. In that case, it became law anyway. Each branch, including the judiciary, was designed to hold some form of leverage over the other two.

Since human nature is fallen, any public officeholder could be consumed by a lust for power. Thus, the system was structured to prevent any one person or clique from gaining too much clout. As Madison put it:

This policy of supplying by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, both private and public.

One person’s selfishness, in other words, would be strategically pitted against another’s. This principle, it was hoped, would maintain healthy, productive tension throughout the entire federal government.

And just when you least expected a C.S. Lewis quote:

You may think all men so good that they deserve a share in the government of the commonwealth, and so wise that the commonwealth needs their advice. That is, in my opinion, the false, romantic doctrine of democracy. On the other hand, you may believe fallen men to be so wicked that not one of them can be trusted with any irresponsible power over his fellows.

That I believe to be the true ground of democracy.

He wrote those words well over a century after the Founding. And yet, you can see how Lewis, a British citizen, recognizes the same principle: since human nature is fallen, the power that one citizen is able to wield over another must be limited.

What this shows is that a separation of powers, as required by the Constitution, is consistent with a Christian view of human nature. As Genesis 1 tells us, human beings were made to reflect God’s goodness throughout the world. Yet, as Genesis 3 reminds us, we also fell into sin. Our system of government, as designed, pairs brilliantly with this reality.

Of course, that doesn’t make it foolproof. Madison also wrote this:

Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation. No theoretical checks—no form of government can render us secure. To suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people, is a chimerical idea.

By that, he meant it was a fantasy that the American republic could survive without its people maintaining some level of virtue.

This, as it turns out, is the challenge faced by a country striving to maintain liberty. The system of government has to be built to withstand the fact that immoral people will gain power sometimes. And yet, at the end of the day, a “system of government” is just people carrying on according to an established blueprint. Likewise, civic “guardrails” are just people who do the right thing even when it costs them. If virtue becomes too scarce, even the best system can fail.

In the end, it all comes down to people, virtue, and the grace of God.

As Christians, we’ve heard the gospel. We believe in the good news that the King who died for our sins and rose from the grave is now seated on the highest throne—and that He will return.

Thus, even the best human government is but a dim shadow of what’s coming. Yet, the Bible also teaches us to protect, preserve, and wisely use the gifts we’ve been given right here. We often call this stewardship.

And if our Constitution, with its separation of powers, isn’t a gift worth stewarding, what is?

WE the People have known the great dichotomy between government and the common man in every generation.

Call it what you will— Federalist, a partial Democracy, a limited Republic, Whig, Loyalist, Democrat-Republican, Progressive, Bull Moose (or just more bull of its incumbent hold on the capital of a capitol) — government is not, and has never been exercised by the majority of All the People at any moment in history, but by political leadership taking claim of a unified claim of a plurality of those involved.

Virtue? You’re right. WE the People cannot claim it and neither can and party of any name or claim.

In fact, God will prevail even though the Lord Jesus Christ seemed to steer clear of the politics of the Kingdom. And today, in 2025 of the Common Era, Christians are dual citizens of our unvirtuous countries lacking in virtuous leadership— WE are such a remnant minority unable to elect anyone on our own— yet we are the Elect of His Kingdom to come, on earth as it is in Heaven.

I don’t know about you but I am still listening for a still small voice evangelizing Christ— a voice lost in the loudness of ‘christians’ evangelizing some powerful political leader or virtual-religious agenda.

The court of public opinion may be bought— and elected— but only for a brief mortal moment.