Grit Can Reveal Grace

Are you sure your zealous brothers and sisters are legalists?

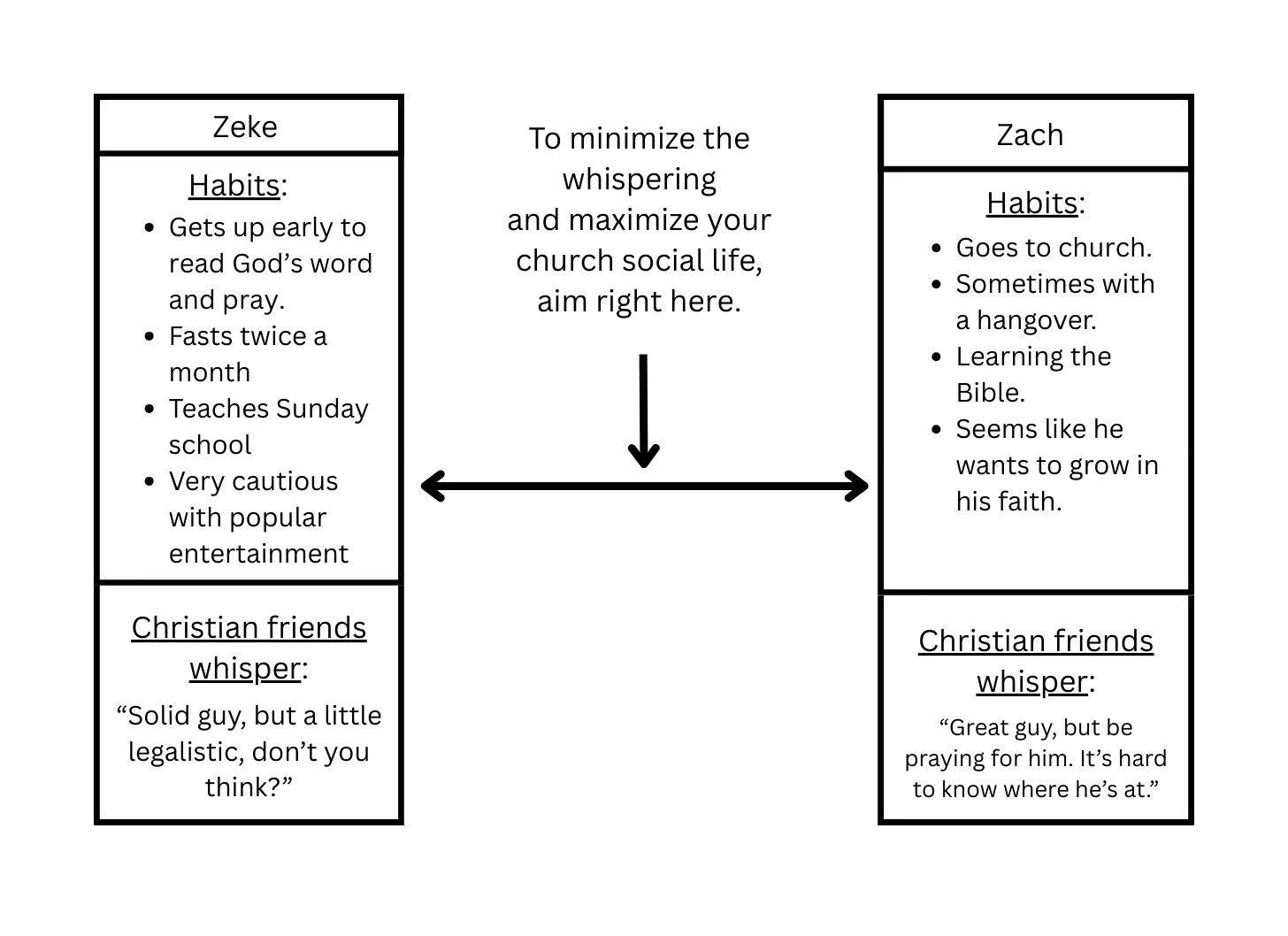

Let’s imagine a pair of twins separated at birth, Zeke and Zach.

Despite growing up in different families on opposite sides of the country, both brothers become Christians in high school.

And while both are still attending church in their mid-twenties, their lives look vastly different by this time. Zeke wakes up at 5 AM each morning to read his Bible and pray. He fasts twice a month and often teaches Sunday school. He hasn’t watched an R-rated movie in years.

For his part, Zach shows up to church almost as often as his brother, but sometimes it’s with a self-inflicted headache. See, Zach’s been known to have a few drinks on Saturday night. Even so, he seems to be a sincere Christian. He’s slowly gained a good grasp of the Bible. He’s honest about his faults, and he drinks less frequently than he used to.

Zeke and Zach are a thought experiment, not real people. And yet you might know believers who fit those profiles. Maybe one or the other even reminds you of yourself.

Are you the rule-following Christian who’s seen as leaning toward legalism?

Or more of the lax, carefree type, who tilts toward an attitude of license?

In church circles I’ve known, people often assume a believer fits one of the two molds. This idea is often unspoken, influencing our attitudes like a river’s undertow. Other times it’s presented plainly.

And I know this generalization rings true for many. But the framing still strikes me as too tidy. Last fall, in a post about God’s grace and Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s tenacious ministry, I wrote:

I think this [idea that most people are tempted by either legalism or license] is an oversimplification, personally. But even if it’s a fair generalization, the idea can still nudge us in the direction of a serious mistake. It can lead to the assumption that if a believer makes a lot of effort to obey God’s word, that person probably has a legalistic streak. This, in turn, sets the stage for making mediocre, half-hearted Christian living seem like the ideal.

After all, as the logic goes, too little obedience might be a sign of spiritual carelessness or license. But on the other hand, too much obedience might be a sign of equally dangerous legalism. Splitting the difference then can be assumed to be the sweet spot. The safe option then seems to be making some effort to grow in Jesus but not too much, to avoid being labeled a legalist.

I still agree with this, and this time I’ll throw in a diagram for good measure. I’ll even give it some juicy gossip (by church standards).

Again, if you want to insist that every Christian you know is either a Zeke or a Zach, that’s fine. I’m not too concerned with how applicable the generalizations are. My question is whether this framework could do harm as well as good.

Consider the charming believer who succeeds at splitting the difference between the two poles. Are we really sure this person is steering clear of legalism? It depends how we think about the concept.

In every church I’ve ever known, you’ll find social acceptance as long as you avoid profanity and the “big sins.” Don’t cuss, don’t have sex outside of marriage, and ideally don’t get addicted to anything. If you are an addict, you’ll still get by as long as you can keep your sin reasonably private. You’ll eventually make friends in any church if you can be polite and follow those rules.

Wait, did I say rules? Yes, Christian culture is guided by the unspoken rules I just mentioned. If you can follow them, you’ll gain favor. If you can’t, you likely won’t. People may still be nice to you (we’re Christians, after all!), but you won’t find the same level of acceptance.

Of course, there’s a distortion on display here. The purpose of following Jesus isn’t to gain social status in the here-and-now. It’s to receive everlasting life and help others to do the same. But this gets to my point. We recognize that a Zeke could, at least in principle, be offering up a superficial moral performance. Likewise, many churchgoers abide by the simplified rules of moral performance that I described earlier. Those who do so could very well land at the sweet spot of acceptance in the diagram above. Meanwhile, their motivations could be just as misguided as that of a (genuinely legalistic) Zeke. They just have fewer rules to follow!

Let’s come at this from another angle. We just saw how the “middle of the chart” Christian could be embracing a subtle form of legalism. Now let’s ask whether someone like Zeke is necessarily a legalist.

To think through this, let’s look to the apostle Paul. And let’s be plain, the man was a fanatic. Even as he leapfrogged from tightly-wound Pharisee to ardent Christian, his type-A disposition remained. I’m reminded of this by 1 Thessalonians 2:8–9:

We loved you so much that we were delighted to share with you not only the gospel of God but our lives as well, because you had become so dear to us. Surely you remember, brothers, our toil and hardship; we worked night and day in order not to be a burden to anyone while we preached the gospel of God to you.

It’s humbling to remember that Paul often funded his ministry by working as a tentmaker. Apparently, he pulled this off by putting in very long hours. In modern church culture, someone laboring as relentlessly as Paul would likely be considered a workaholic. Maybe even a legalist. After all, if you really understood that your salvation was made possible by what Jesus did for you, couldn’t you chill out a little?

Paul surely enjoyed some times of rest, but likely not nearly as many as we’d expect today. Consider 2 Corinthians 11:24–28:

Five times I received at the hands of the Jews the forty lashes less one. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I was stoned. Three times I was shipwrecked; a night and a day I was adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from robbers, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, in hunger and thirst, often without food, in cold and exposure. And, apart from other things, there is the daily pressure on me of my anxiety for all the churches.

Suffering and persecution aren’t the same as self-imposed acts of obedience. Yet the symmetry isn’t hard to see here. Paul’s willingness to repeatedly throw himself into difficult situations fits with the lifestyle of “night and day” toil that he described in 1 Thessalonians. Calling him zealous for good works would be an understatement.

And so we arrive at the paradox of this great saint. If anyone might have appeared to be trying to earn his salvation, it was Paul. Meanwhile, he’s the go-to guy in the Scripture on salvation by grace. Romans 3:22–24 is but one of many examples:

This righteousness from God comes through faith in Jesus Christ to all who believe. There is no difference, for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and are justified freely by his grace through the redemption that came by Christ Jesus.

There’s no doubt many have found the “legalism versus license” framework helpful. At the same time, if we could see into the depths of the human heart, I wonder if we wouldn’t find this paradigm upended.

Maybe the people with the deepest appreciation of God’s grace are those whose lives are filled with the most astonishing works. Paul is surely an example of this. Modern-day believers like Corrie ten Boom, Brother Andrew, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and Richard Wurmbrand point to the same conclusion.

Why is this? Maybe a deep appreciation of the Lord’s mercy is the very thing that forges vibrant, obedient souls. Possibly it’s because vigilant faithfulness makes our need to rely on God all the more evident. A Christian who makes a half-hearted effort might cling to the illusion that more rule-following could yet deliver him to a higher spiritual plane.

But the one who’s exhausted himself through obedience knows the foolishness of that. And so this weary believer looks, once again, to Jesus on the cross. This depleted saint turns to the One who accepted every human limitation. He relies on the One who endured insults and suffering. He again surrenders his life to the One who entered the grave, only to rise from it and shatter its power. And it’s then, reassured of the Father’s love and renewed by the Spirit, that this soul discovers the strength to carry on.

It is ironic that we can't work our way into heaven, but when we truly understand what Jesus did for us, we want to ceaselessly work in service to our Lord. The difference isn't the works, but the heart that motivates the works.

Very few people realize that the intersect of Law and Grace is that the giving of the Law is an act of covenantal grace.

God’s Law, which is His expressed will for our lives, marks us as His people and prescribes a life which is good for us.

A life of grace divorced from law is a hellish life. A life of law divorced from grace is a life of condemnation