Every Generation Must Hear This Story

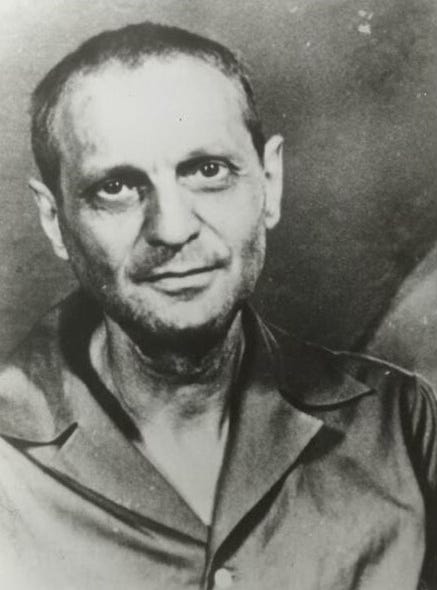

The enduring voice of Richard Wurmbrand

Richard Wurmbrand’s story must be told. And yet, how to share it?

Beginning in the late 1940s, the Romanian Lutheran pastor endured two separate periods in prison for his faith. Over a total of fourteen years, he suffered extraordinary cruelties at the hands of his nation’s Communist regime.

From his 1967 book, Tortured for Christ, it’s clear that Wurmbrand himself wrestled with how to share some aspects of his testimony. On the one hand, his account is searing and direct. He writes that “all the biblical descriptions of hell and the pains of Dante’s Inferno are nothing in comparison with the tortures in Communist prisons.”

Yet he withholds specific descriptions of some of the things he saw and experienced. After recounting a particularly graphic humiliation suffered by a priest, Wurmbrand writes, “Other things simply cannot be told. My heart would fail if I should tell them again and again. They are too terrible and obscene to put in writing.”

How do you share a story with parts too terrible to tell?

How do you shine the light of Christ into an unfathomably dark place?

For Wurmbrand, one key is recalling how it will all end. He transcends the wretchedness of prison by remembering the glorious future that awaits those who suffer for Jesus.

I had around me men like Lazarus the beggar, hungry and covered with boils. But I knew that angels would take these men to the bosom of Abraham. I saw them as they will be in the future. I saw in the shabby, dirty, weak martyr near me the splendidly crowned saint of tomorrow.

His hopeful vision even extended to his tormentors.

But looking at men like this—not as they are, but as they will be—I could also see in our persecutors a Saul of Tarsus—a future apostle Paul.

Wurmbrand writes that he witnessed many officers of the Communist secret police come to faith in Jesus. Again and again, it was the compassion of the very Christians they afflicted that eventually opened their hearts. It was the faithfulness of those who truly loved their enemies.

During his imprisonment, this irrepressible, Christlike love took hold of Wurmbrand. Consider this encounter, following his imprisonment, with Western believers who had come to Romania:

[These believers] told me that they had heard that at this address there was someone who had spent fourteen years in prison, and they would like to see him. I told them that I was the man. They said, “We expected to see someone melancholic. You cannot be this person because you are full of joy.”

Yet another difficulty of telling Wurmbrand’s story arises. Here, it’s tempting to shoehorn his life into a trite takeaway: remain faithful and you’ll know joy no matter what life throws at you!

There’s truth to that tidbit. But there’s also a tidiness that betrays what Wurmbrand—and countless other persecuted Christians—have experienced.

That’s one reason it’s worth reading Wurmbrand’s account, or another like it, in full. It takes time to consider the deep contours of such a harrowing experience. Brief retellings can seem mired in contradictions. Yet, a lengthy reflection will reveal credible paradoxes: the pastor’s mind fiercely rejected communism while his heart overflowed with mercy for communists. His unfathomable suffering brought forth a deep wellspring of joy in Christ.

I chose Wurmbrand’s story because of its relationship to Brother Andrew’s, which I shared recently. Andrew’s clandestine ministry delivered Bibles behind the Iron Curtain. He even traveled to Romania in 1957. Years later, he and Wurmbrand would meet.

While the lives of the two men clearly had parallels, the contrasts are starker. Brother Andrew, astonishingly, was never imprisoned during his years of Bible smuggling. Many consider this fact to be a miracle.

Wurmbrand contends that he too experienced a miracle, although one of a very different kind. Without supernatural intervention, he feels certain that the abuses he endured in prison would have killed him.

Again, how do we tell a story like this? Do we recall it with awe that moves us to worship God? Or do we tell it with anger? Or with fear? How do we account for the workings of a God who wields supernatural power, yet allows his beloved people to suffer the unspeakable?

Perhaps we simply have to stop. We have to let go of our efforts to make intellectual sense of it. And then we can join with Paul in saying, “Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!” (Romans 11:33)

Then with ears to hear, we can return to voice of Richard Wurmbrand:

One great lesson arose from all the beatings, tortures, and butchery of the Communists: that the spirit is the master of the body. We felt the torture, but it often seemed as something distant and far removed from the spirit which was lost in the glory of Christ and His presence with us.

Thank you so much for reading. In a couple of weeks, give or take, I’m going to follow up with another post on Wurmbrand. There, I’ll consider some of the direct challenges he presents to readers in his book and how we might respond.

In the meantime, you might take a look at The Voice of the Martyrs, the organization he founded.

Have a blessed week!

Thank you for this. My father was Christian author Dave Hunt. Richard Wurmbrand was a friend of our family. I will never forget when he, his wife and his son came to stay with us shortly after he was got out of Romania and came to the United States to testify before Congress. I was 9 years old when I met him and will never forget the experience. He had a huge influence in my life and I have included him in some of my essays. We also knew Brother Andrew. In 1967, my family smuggled Bibles into Romania, a very dangerous journey. The tears of joy when people received the Bibles is forever imprinted on my memory. Christians in the West have no idea what it means to suffer for Christ but perhaps that day is soon to come.

I wrote about Wurmbrand here https://khmezek.substack.com/p/no-greater-love-than-this

🇷🇴 MEMORY ETERNAL! 🕯️