Atonement's Imprint

Psalm 139 doesn't mention salvation. It doesn't have to.

When you take up a life immersed in God’s Word, sooner or later you run into the idea of a paradox. You won’t find the word itself in Scripture, but once you come to grasp the concept, you discover it’s all over the place.

Gotquestions.org has this definition:

A paradox is a seeming contradiction that, when properly understood, may prove true.

And the Bible is filled with seeming contradictions that do prove true. Consider one of its most famous:

Jesus Christ is fully God. And Jesus is also fully man.

Long-time Christians can get so used to this truth that we forget how impossible it seems to many. Skeptics may find it laughable. Some other religions find it downright offensive. And yet it remains utterly true.

Psalm 139 is among my very favorite psalms, and it offers a wonderful paradox to contemplate. It presents a God who is holy, yet present with sinners. Though not explicit, this idea is reasonably drawn from the psalm. Here’s a way to think about it: imagine finding a piece of clay with a handprint in it. No one else is around, but because you know what a hand looks like, you know with certainty how the imprint was created. Likewise, Psalm 139 bears the imprint of Jesus’ atonement for our sins.

Consider how the psalm begins, with a rich reminder of God’s nearness:

O Lord, you have searched me and known me!

You know when I sit down and when I rise up;

you discern my thoughts from afar.

You search out my path and my lying down

and are acquainted with all my ways.

Even before a word is on my tongue,

behold, O Lord, you know it altogether.

What’s going on here is more than cold, supernatural surveillance. Verse 13 presents a compassionate God, one actively involved with human life, even from its earliest stages:

For you formed my inward parts;

you knitted me together in my mother’s womb.

Relatedly, verses 9 and 10 reveal a God who is deeply engaged with the psalmist, able to guide him wherever he goes:

If I take the wings of the morning and dwell in the uttermost parts of the sea, even there your hand shall lead me, and your right hand shall hold me.

Here, we discover a communion between the divine and the human. In an era where it’s common for people to speak of Jesus as a friend, this may not startle us. But in the Old Testament, even faithful people often feared a direct encounter with the holy God.

And that fear wasn’t unfounded. In Exodus 33:20, God warned Moses that “you cannot see my face, for man shall not see me and live.”

Another example of the fear of God involves the prophet Isaiah. In chapter 6 of the book that bears his name, he experiences a radiant vision of the Almighty upon his throne. It’s complete with angelic beings who cry out, “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts!” This is how Isaiah responds:

“Woe is me! For I am lost; for I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips; for my eyes have seen the King, the Lord of hosts!” (Isaiah 6:5)

It’s a pretty far cry from “your right hand shall hold me.” But then the Lord of Glory does something unexpected. He sends out an angelic being called a seraph with a mysterious object. Here it is from Isaiah’s perspective:

Then one of the seraphim flew to me, having in his hand a burning coal that he had taken with tongs from the altar. And he touched my mouth and said: “Behold, this has touched your lips; your guilt is taken away, and your sin atoned for.” (Isaiah 6:6–7)

So what is this burning coal that provides atonement? I’m not sure that’s quite the right question. Instead, we might ask who the coal foreshadows. Hundreds of years after Isaiah, the answer becomes clear:

Jesus Christ, the Righteous One. . .is the atoning sacrifice for our sins.

(1 John 2:1b–2a, NIV)

The word “atonement” was first used in a theological sense by William Tyndale in the 16th century. While translating the Bible, he struggled to come up with an English word that could express the idea of a holy God reconciling himself to sinners. Apparently in a literal frame of mind, Tyndale chose a word containing “at-one-ment” within. Through Christ’s death on the cross, God made it possible for us to be “at one” with him, reunited with his presence.

Earlier, in Psalm 139, we saw how the psalmist is led by the hand of God. This reflects the miracle of the atonement. Just as Isaiah could be reconciled to God centuries before Jesus came to earth, so too could David. And although the clearest mentions of sin in Psalm 139 involve God’s enemies, David himself was far from sinless. In Psalm 51, he recalls his adultery with Bathsheba and pleads for the Lord’s forgiveness. “My sin is ever before me,” he says in verse 3.

Yet even in these depths, David knows that he’s calling out to a God who atones for sin. “Restore to me the joy of your salvation,” he says in verse 12.

Though the circumstances in Psalm 139 are different, the psalmist is likewise aware of sin’s danger. In fact, he ends by asking God to bring to his attention any trace of disobedience that lurks within him:

Search me, O God, and know my heart!

Try me and know my thoughts!

And see if there be any grievous way in me,

and lead me in the way everlasting!

(Psalm 139:23–24)

May we join with him in that prayer. And may we more fully experience what it means to be reconciled to a holy God—everlastingly.

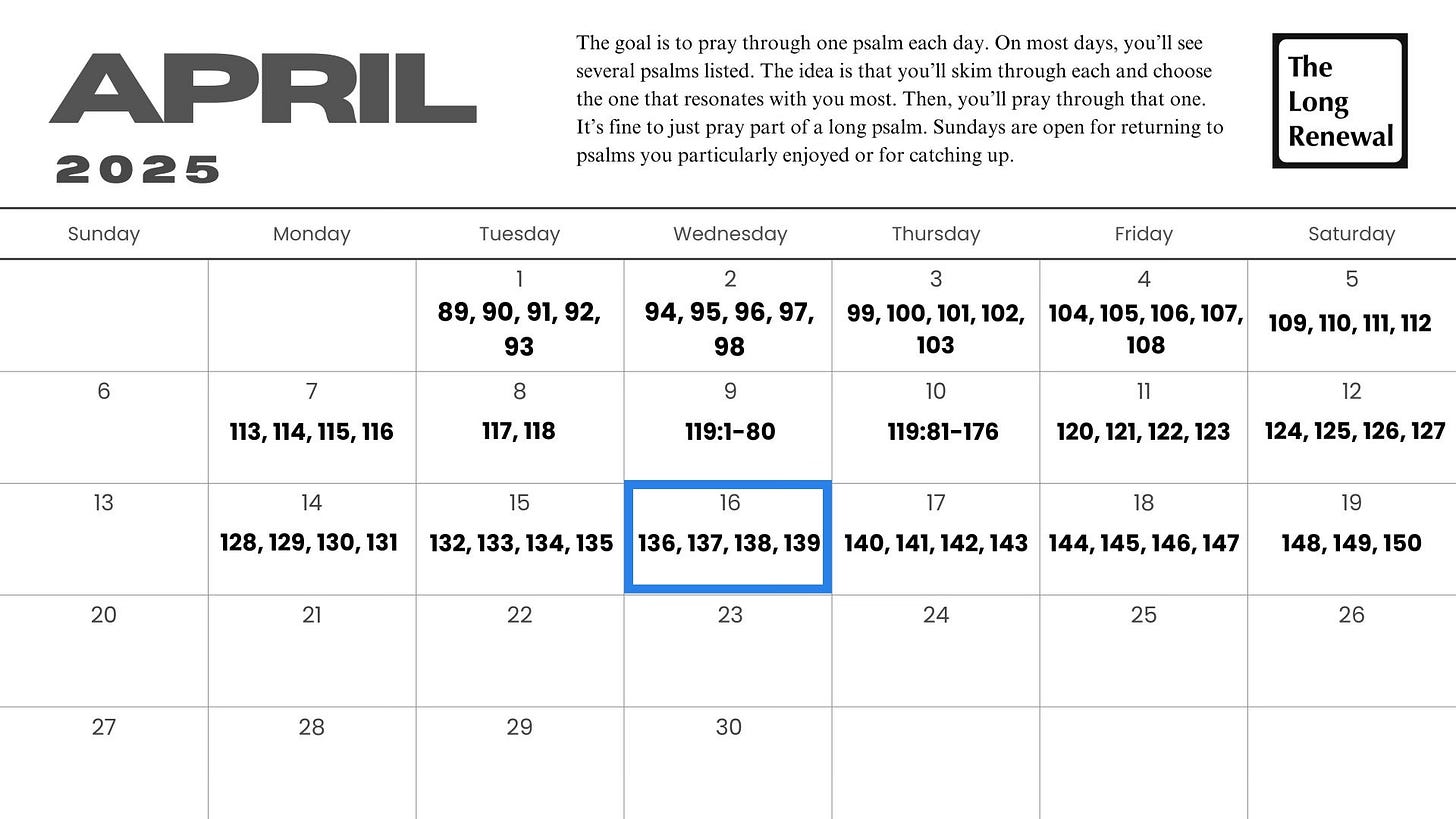

If you’ve used the psalm prayer calendar at all, I’d really appreciate hearing about your experience with it in the comments.

If you haven’t, just go pray through Psalm 139 right now. Then comment!

Thank you so much for reading and have a blessed Good Friday!

Thank you!